Explosive Tonga -- Volcanos and Riots and Democracy

For about six years now I've been kidded by my friends and family about Tonga. I was depressed with the outcome of the 2000 elections; about the rigged votes; about 9/11; about the lies and missed opportunities leading up to the invasion of Iraq; about the destruction; about the moral hypocrisy that seemed to be coming from an unelected administration bent upon consolidating its power.

For about six years now I've been kidded by my friends and family about Tonga. I was depressed with the outcome of the 2000 elections; about the rigged votes; about 9/11; about the lies and missed opportunities leading up to the invasion of Iraq; about the destruction; about the moral hypocrisy that seemed to be coming from an unelected administration bent upon consolidating its power.

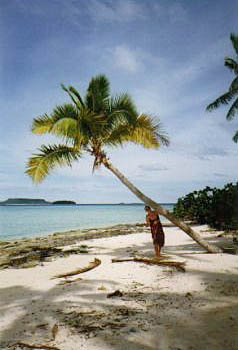

I was immersed in books that recorded the world travels of past generations of sailors, actively seeking a safe haven where corruption, where it occurred, was on more on a scale of human failings than institutional decay. Scale, beauty, simplicity, safety, and humanity: These were the goals. More and more, I found my mind turning to descriptions of the island kingdom of Tonga.

I'd complain and quip about what was going on this country, and eventually people would ask: So what are you going to do about it?

"I want to move to Tonga!" became my response.

Tonga! Tonga! The dream of an island kingdom in the South Pacific! Lots of sailing! Beautiful people! Simplicity! Life! Maybe another chance for happiness!

I'd laugh at myself, along with everyone else, but once inoculated with the idea, the dream seemed to take on a life off its own.

"I'm a writer! I can work anywhere!"

"So where do you want to be?"

"Tonga, maybe! I think we should move to Tonga!"

Meanwhile, Tobias came back from Europe and started college in Pennsylvania. Arwen tried Pennsylvania and returned to California with me. Dagan meandered between Northern California, Southern California, and Oregon. Judith was teaching in Pennsylvania. I felt like I was holding down the fort in St. Helena while the world was collapsing around me.

"Tonga, maybe!" I kept saying to myself. "Maybe in Tonga I can figure all this crap out!"

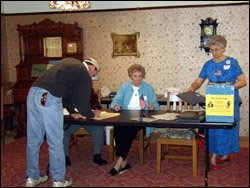

By the time the 2004 elections arrived, my disgust with the direction things were moving here had reached a new low. "When are people going to finally wake up?" I demanded. I had done a little election work in Pennsylvania, acting as an election observer at the polls: Helping to roll in the huge, ancient polling machines; helping people with instructions before they entered into their booths; checking peoples' names off of election rolls; helping  to tabulate ballots off the continuous-roll ballot machines; cross-checking the results; talking with the volunteer election officials at the little church where I was stationed.

to tabulate ballots off the continuous-roll ballot machines; cross-checking the results; talking with the volunteer election officials at the little church where I was stationed.

I began to see the election process in the U.S. as an embodiment of those ancient gray machines with their faded black-velvet curtains and their worn, painted levers -- rows and rows of levers aligned into columns of parties, candidates, issues, and initiatives. And the election volunteers themselves, so happy to have someone new to help them out in the basement of that little brick church. They were lovely elderly people from the neighborhood, gray themselves like the old mechanical machines, and slightly frayed at the edges like the velvet curtains. Blue-haired old ladies directed by an earnest old man. Even I, nearing retirement age, seemed young to them. They were as old as the balloting machines themselves, and it seemed that in their eyes they were looking to me, with a bit of hope, that I might take up their work at the next election.

"Tonga!" my heart murmured in denial. "Tonga!"

One of the balloting machi nes became stuck. It jammed in the middle of someone's vote-casting. It was stuck solid, and the master lever could not be budged. "No problem!" said the elderly man in charge of the precinct. He moved the voter to another machine, and then -- with my help -- we rolled the broken machine aside, opened the back through a set of shiny polished spring-mounted screws, breaking the metal election seal. He could not do it alone, not because the machine was too heavy, but because I was to act as a sworn witness to what he was about to do.

nes became stuck. It jammed in the middle of someone's vote-casting. It was stuck solid, and the master lever could not be budged. "No problem!" said the elderly man in charge of the precinct. He moved the voter to another machine, and then -- with my help -- we rolled the broken machine aside, opened the back through a set of shiny polished spring-mounted screws, breaking the metal election seal. He could not do it alone, not because the machine was too heavy, but because I was to act as a sworn witness to what he was about to do.

The back of the machine opened downward to reveal the continuous roll of paper, pre-printed with names of candidates, party affiliations, and ballot initiatives for local and county issues. The recordings of each person's vote had been marked like mechanical chicken marks on the roll as the master lever had been pulled. Each vote, a series of punches permanently imprinted beside each candidate.

As I looked into the mechanism of this machine, with its cogs and levers, I felt as though I were looking into brain of the democracy itself: Heavy, technologically ancient, complex, adequately oiled and cleaned, but worn by sixty years of occasional intense usage. It was an artifact of an industrial age that had long since been surpassed by electronics, but still it persisted to stand. I was faced with the fragility of that democracy, yet chastened by the intensity with which the election official performed his volunteer tasks.

intensity with which the election official performed his volunteer tasks.

"These machines are older than I am," he said as he drew a line through the spoiled ballot on the machine. "Sometimes they just jam like this, and all you can do is mark where the last ballot ended. He pulled out his clipboard and had me read off the dial of numbers in that indicated how many ballots had been cast on the machine that day. 321 ballots! Then he had me read off the number of ballots that had ever been cast by the machine in its lifetime. I don't remember the number, it was so large. He had me read off these numbers three times, marking them down on his clipboard. Then he signed the clipboard, made a note on the huge roll of paper, signed the roll, had me sign his clipboard, and recorded the date and the time. Then we closed up the massive machine and, together, we rolled it out and down the hallway by the stairs.

"Tonga!" my heart murmured. But the sound of it was a little fainter, a little less intense, a bit like an echo of a desire.

Later, as we closed up the polling place, I thanked the poll workers for the experience. It had been a long night, reading off the numbers off the balloting machine, calling the numbers back and forth, checking and cross-checking each others' work. We had formed a kind of team, and we made little quips about what we were doing as we worked. No one spoke of politics. This was just another job, like raking the leaves or straightening the folding chairs into rows at the end of a church social. We were straightening up after a national election like we were straightening up after a dance. It was a strange sort of dance, indeed. But we were tired. Some of the blue-haired poll workers had been there all day, and they were hungry. I'd been there no more than three hours. I said goodnight and walked out into the rainy darkness and drove to Judith's house.

"Tonga?" my heart now seemed to be questioning me. "Tonga?"

That night my desired Presidential candidate, John Kerry, took the county and ultimately the state of Pennsylvania. I had not voted in that polling place where I worked. I knew I would probably never see those poll workers again. Their looks seemed to be asking for someone new to pass the baton of electioneering, but I knew it would not be me who picked it up. Still, I was humbled by their dedication to an idea about democracy; chastened by their matter-of-fact belief in the process; awed by their persistence to "get it right", "double-check it", "Did you get that number Gladys?" It was like watching my parents do the dishes together so long ago: Doing the dishes of an election.

Tonight I read the news from Tonga on the Internet.

In September, King Taufa’ahau Tupou IV died at the age of 88. The royal family was just completing the traditional period of 100 days of morning.  To mark the official ending of the 100 days of mourning period for the Royal Family the Lanu Kilikili ritual or the Washing of the Stones will be held at the Royal Tomb at Mala’ekula, Nuku’alofa to be carried out by the Ha’a Tufunga. The newspaper said that they have just started receiving the fine stones that have been carefully selected from the shores of the volcanic island of Tofua.

To mark the official ending of the 100 days of mourning period for the Royal Family the Lanu Kilikili ritual or the Washing of the Stones will be held at the Royal Tomb at Mala’ekula, Nuku’alofa to be carried out by the Ha’a Tufunga. The newspaper said that they have just started receiving the fine stones that have been carefully selected from the shores of the volcanic island of Tofua.

But then, last Wednesday a riot broke out as some drunken teenagers got hyped up after a pro-democracy protest that had been going on all week in front of the new king's administration office.

Cars were overturned. Grocery stores were ravaged. Windows were broken. Fires were set. Fortunately, no one was killed.

If you're interested in my double life in Tonga, you should check out this story at Matangi Tonga Online.

It's clearly been a tumultuous time for the Tongan people. In another story on the newspaper, a new volcano is breaking the surface of the ocean in the Kingdom of Tonga. Huge rafts of floating pumice clogged the engines of boat that was the first to actually witness the erupting volcano.

In other news, the electrical utility in Tonga has created a big stir. The electrical utility had been privatized a couple of years ago, but now wanted the government to buy back the assets. The price of diesel fuel to run the generators had ruined the profitability of the company, and it was threatening to sell the assets to Chinese interests. Instead, it was decided to sell the power company to a New Zealand firm. There's still some legal issue about whether the original privatization was constitutional to begin with.

All this is sound ing hauntingly familiar.

ing hauntingly familiar.

....my sail boat has been sitting on its trailer for a year. Judith thinks I should sell it and get a smaller boat. I don't know.... (...."Tonga!... Tonga!... Tonga!...)

I miss Tonga, having never ever set foot on the tiny island. I miss the Tongan people, having never met a single one. I miss the ceremonies, the island winds, the coral beaches and the palms. My heart still calls out "Tonga!" and I worry about their riot, their volcano, and their electricity.

But here, in Northern California, the leaves are blowing off the trees and the grape vines. It is time for Thanksgiving, after an important election. Tobias is in Cambodia now, but Arwen and Dagan and Kellie and Judith will all be at the dinner table.

The volcanoes are silent in my heart. The riots have been, for the moment, silenced.

I think I'll pour a glass of wine at the Thanksgiving dinner table and propose a toast.

"To Tobias and Tonga!" I'll say.

And, of course, everyone will kid me.

But I think I'll be okay now.

2 comments:

I too had similar visions of a Tongan refuge. I went six months ago and here’s a little of what materialized of my Tongan escape.

I found that the small American company that I got a job at that led to me going there was as crooked as can be, but at least it was other Americans that they were fleecing, not Tongans.

Tonga is not a tropical paradise, it is a litter strewn, dirty, impoverished island. The people are clean, but everything else is filthy. The beaches are littered, the streets are littered, dirty diapers are dumped in mass on the sides of roads. Anything that a hand touches multiple times is coated in dirt, door frames etc. Sanitary anything is nonexistent, that includes restaurants, hospital, stores, etc. And when it rains, things get much dirtier, not cleaner.

Dogs are a problem everywhere. They are roaming the streets everywhere. Skinny, ribs showing, with long hangy nipples from their multiple litters; all roaming looking for any morsel of food that will prolong their suffering another day.

Kids are great, they still know how to play with out electronic gear. They are out in the streets playing street games and marbles, and flying home made kites.

Seeing Tongans with woven mats around their waists becomes normal, it doesn’t even look strange after a while, in fact I started to like them.

Getting to know Tongans was great. I loved learning about their culture and view on life. Kind of a, “relax, don’t worry” attitude. I got very used to kids saying “bye” when they came towards you on the street, not hi. I liked the giggles and the word palangi interspersed with the giggles as they passed chattering to their friends.

I felt bad about the corruptness of the government their, and of the royal family. The only respected ones by the Tongan commoners unfortunately were the prince and princess killed in California while we were there. They were working towards democratic reforms.

My wife did some work for the democratic movement and got some insider knowledge of all that they must overcome with the deck so stacked against them. I’ve read the reports of gangs of criminals and drunken youth rioting. While there is some truth there, I wonder how our own revolutionary war would have sounded spun that way? The Boston tea party wouldn’t be a “tea party” it would be a riot of drunken criminals run amok.

We left a few days prior to the riot. We wonder what the friends we made there have to say. We say on another blog a picture of one good friend’s internet café burned out. We wonder if she will recover? But we also know that during the revolutionary war there would have been plenty of those stories that didn’t make it into the history books and cultural lore, that was tragic to the individuals harmed, but led to a good outcome.

I hope you keep your Tongan dream going, who knows, maybe you’ll go and find a different story than I did.

Is it possible that life on an island is like living in a closed community? Everything is public, everything is "status", everything is predefined by previous generations?

What is left for teenagers to rebel against? (Everything!)

Is it the "commune syndrome"? In the early 70s a lot of us made the push with communal living. My experience was limited to a year in communal house in Southern Vermont.

A lot of what you describe in your visit to Tonga sounds like my experience in that environment. A million animals running free through the house, copulating everywhere; people doing very unsanitary things and not picking up after themselves; lots of garbage and no one taking responsibility. Of the nine or ten people who lived in that house with me, I've remained friends with only one!

But then, maybe I'm just reading in a lot of my disappointment into your experience.

Teenagers! On an island!

That, in and of itself, must be a really difficult construct.

Thanks for dropping by with your comment.

Post a Comment