5:30 AM. I stumble to the phone that has awakened me from a deep sleep. It's Peace Corps in Washington, DC. Somebody name Danielle Smith. They've received our medical forms, but -- on mine -- there's a problem. They had my SS# wrong, so I'd crossed it out on the forms and put in the right one. Now they want to know why. I told them the preprinted SS# was inaccurate. So they want me to fax them a signed statement explaining why I had changed this. Argh! Bureaucracies!

The voice on the other end is patient as I struggle to find my glasses and then careen through the house looking for something to write down their fax number. Finally she says "I'm sorry if I woke you or sumtin."I said, "It's okay! I had to get up to answer the phone anyway!"

Sumtin! The inflection of Ms. Smith's voice makes me remember the inflections of friends we knew back in DC in 1972. A flood of memories comes back, when we lived on East Capitol Street, ten blocks from the Capitol, on the edge of Lincoln Park.

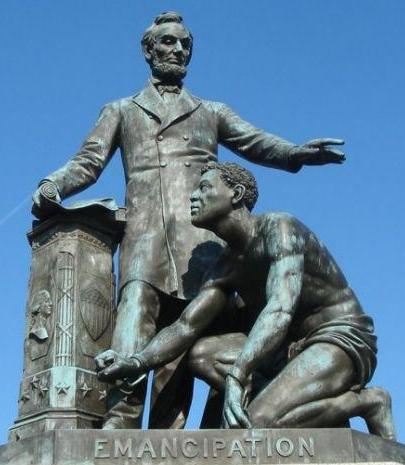

We lived on the top floor of a three story house amid brownstones, directly across from the park, where a large statue entitled "Emancipation" stood. It was a statue of Lincoln reaching down to a slave. Every morning I arose early to move the car because the street changed direction to accommodate the influx of traffic. If I slept late, my car would be ticketed and towed, and many a morning I arrived just in time to prevent the tow trucks from hooking up to our old Saab 96.

And every morning the park was the playground of greyhounds that ran the length of the green, chasing the pigeons that roosted everywhere.

Judith wrote a beautifully frightening poem about Lincoln Park during our time there.

Our housemates were the Baycotts - an African American family with five beautiful young children. They lived on the bottom two floors, and Mrs. Baycott took a special interest in Judith, who was nearing full term with our first child, Dagan.

The inflection of "somtin" by Ms. Smith made me start thinking of Mrs. Baycott and those beautiful kids.

One evening, as we climbed the stairway up through the house to our third floor apartment -- as we reached the second story loaded down with groceries -- our eyes were caught by a single brown finger of one hand wriggling beneath the door of the second floor bedrooms. First one finger wiggling, then a second, then a third -- waving a silent hello.

Then there was a second hand, then a third, then a fourth, each hand wiggling fingers. Before we reached the landing, five pairs of hands, fingers wriggling, shown beneath the old wooden door. "Hello!" the fingers said. "Ssh! Don't tell Momma we're here doing this! Hello! Goodbye!"

In February of that year our son Dagan was born, and Mrs. Baycott daily came up to attend Judith and to see the new baby. I recall how she sat in the chair by the third story window, baby between her hands, looking deeply into his newly opened eyes. She was such a help, curious about the name we'd given to him, present but distant, somehow separated from us, but deeply engaged in our new adventure.

"Isn't he sumtin!" I remember her saying. "He's such a beautiful boy!"

After Danielle Smith has hung up this morning, I lay in bed unable to fall back asleep. I can't stop thinking about those old days more than 30 years ago. Ms. Smith would be just about the age of one of those Baycott children, I think to myself. All grown up. And it makes me wonder how their lives have gone, thousands of miles away, growing up in the nation's capitol. Do they each have their own children now? Is Mrs. Baycott a grandmother too? How has life treated them? Do they even remember us, the arrival of the new baby? The chaos of our sudden departure? Did they ever wonder what became of us, just as I now am wondering what became of them?

For me, growing up as I did in the Midwest -- amid racial segregation and cultural stereotypes, in a middle class white family -- trying to emotionally navigate an era of riots and prejudice -- that moment on that flight of stairs so long ago was a kind of milestone of a personal emancipation. The barriers between us seem to break by the simplicity of their silent, waving greetings. Were I to meet one of those grown up children today, I know my fingers would wriggle their own silent "Hello! How's it been for you?"

And then I would whisper "Don't worry! I never told your Momma! But then, I know she wouldn't mind either."