This morning, on the concrete step, beside the pots of plants and flowers that still await their turn with the gardener, there sits a small Cambodian lion. My son Tobias brought it home to us long ago on one of his trips, and at first I didn’t know what to make of it. It’s a curious gift – another curio to join the herd of wooden elephants and the other assemblages of bric-a-brac that inhabit our book shelves.

The lion is very crudely made of an indeterminate metal, somewhat greenish in color, and still black with the grime of a recent forging. It was forged in the shape of the Khmer lions that stand guard over the headwaters of the Siem Reap – a temple lion of the Khmer kings. Its a dog-like figure, with a narrow Khmer dog waist and a large Chinese-style head full of sharp stylized teeth, has a dragon-like ruff running down its spine to the tip of its curled, tufted tail.

When I first held it, I thought it might be made of bronze because of its heft. I thought all it needed was some metal polish brushed on with an old toothbrush to bring out the golden patina that I believed lay hidden beneath the grime. So I went to work on it, polishing and brushing, until my fingers turned an aching green. This lion is no bigger than a mouse in my hand but the grime was so deep and the forging so rough that I could only barely get the slightest glimmer out of the metal. And within a few days, that glimmer was gone again, lost in dark green oxidation. In the end, I gave up, and then sent it on a surreptitious journey across many different stations throughout the house: First it went to the fireplace mantle, then to the oak bookcase in my office, and then, several years ago, to the concrete step where it now guards the front door. How, precisely, it ended at the front stoop is mysterious to me. Perhaps Judith relocated it there, or maybe even Tobias or Arwen. But there it sits, guarding the door, and that’s where I found it this morning.

Meanwhile, my son Tobias has gone off to Cambodia again and again. At first he had gone on a lark, but as each trip ended, he came back a bit more somber. It disturbed me because I couldn’t understand what was changing him.

Then two years ago, just exactly at this time, we went to visit Cambodia where he and his sister Arwen are working. The town is Siem Reap, near the ancient Khmer capital of Angkor, and it was a trip filled with many awakening things.

Arwen took on the role of being our hostess, putting us up and helping us get our bearings. She even became our point person as we bartered in the markets: Too much, too much, she would say. Only two dollar, only two dollar, was the response. Somehow she knew that if she persisted, she’d strike the bargain right where she wanted it.

Meanwhile her brother Tobias – present but in the shadows of our conversations – came and went and came and went again. He was like a kind of ghost; a face remembered; a silent, thoughtful presence just beyond our reach.

Then, near the end of the time he was able to spend with us, he drove us out to the project where he had been working – a great dry basin where a trickle of water ran in the creek, and where two young boys were throwing a net to catch minnows for food.

It was here that I felt we had at last found him. His NGO was constructing a large concrete water gate to dam this creek and flood a reservoir, so that rice paddies could fill and flourish once again. But right now, where we stood inspecting this massive construction site, we were nowhere and in the heart of nothing, as the sun beat down on us on the dry red Cambodian soil, and the boys threw their torn and crudely patched net again and again into the shallow water. His cohort, the monk named Somet, covered himself with his crimson robe, to shade his shaved head from the heat. We looked about, took photos of this moonscape, and tried to imagine the place where we stood someday flooded with water. A water buffalo plied the reeds in the distance. The boys threw the net again. Nothing.

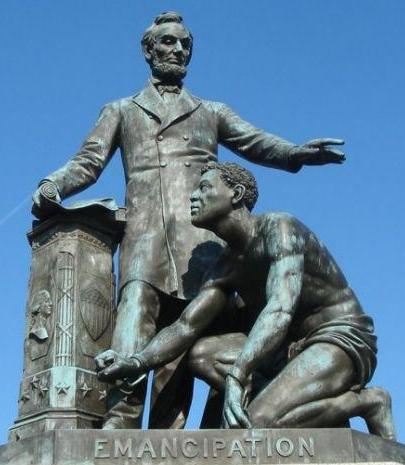

Later, he drove us to Somet’s wat, where there were the ruins of a Khmer monastery, and where stone lions once guarded the temples of the monks. But these lions had been tipped off their pedestals, and their wide mouths had been broken by the rifle butts of the Khmer Rouge years before. Then they dragged an artillery cannon up the rise, up the sacred steps of the monastery, and mounted it on the roof of one of the temples. The roof eventually collapsed, crumbling under the weight. So the canon had been dragged clear of the rubble and now stooped in the grass like yellow giraffe at a water hole, barrels pointing down, waiting for more nothing.

The temples were built in typical Khmer style: Small rectangular rooms called “libraries” connected by long enclosed corridors. Their roofs were made of carefully hewn stones that were tilted against one another to form triangular pyramids. The Khmer engineers had not yet discovered what we today call the Corinthian arch when these building were built. Now many of the libraries and corridors have collapsed and are merely blocks of stone piled through the forest.

In the gray-green jungle, brilliant red signs stuck on spindly poles displayed crude drawings of skull and crossbones to warn of the land mines that still riddled the paths.

The grass was alive beneath the leaves with termites, eating through the forest litter.

Tobias and I climbed down into one of the long ruined libraries of the Khmer monastery. The stones were fitted within a hair’s breath of one another, but the great window lintels had long ago cracked and were now held in place by giant wooden timbers, fourteen inches thick. It was a desperate attempt to save these ancient temples from final collapse, but this technique made the buildings look even more decrepit.

In this damp, cool shade beneath the ground, it struck me how far this solemn young man had come. I remembered how once years ago he had stood leaning against the door jam of my VW bus on a Halloween night half a world away, watching the full moon rise above the vineyards where we lived. Back then, it seemed that door jam was a threshold to his life, and he said “This is the last time I’ll see a full moon on Halloween here.” He was at that time 14. Now he was a full grown man, six feet six inches tall, skinny as a stork, living his life 10,000 miles away, in a haunted place a thousand years old, more frightening than any haunted house we might have imagined. It seemed truly an ancient place of the dead.

But it was the experience in the mine field that focused my attention that day, visiting the site where the CMAC crew was clearing canals that led from the dam. Tobias had driven us as far as he could along the rutted red sand road, through the stumps of brush and trees that had been leveled to the ground. The truck could go no farther because the ruts were deeper than the axel of his truck, and we had to climb out and walk the remaining mile: Tobias and Somet leading the way while Judith and Chai and I followed on the foot path. Along the path all plant life had been mercilessly cut down twenty feet on either side. Every 30 feet a concrete pillar documented that CMAC – the Cambodian Mine Action Committee – had swept for mines.

Eventually we came upon the CMAC crew: Ten men in blue uniforms, some standing beneath a makeshift blue tarpaulin roof strung between two enormous termite mounds. Others were sweeping the area ten yards ahead with metal detectors. They wore no protective clothing other than a plastic face shield. They were searching for anti-personnel mines and unexploded munitions – things they called UXOs for “unexploded ordinances”. I asked if they had found any. “Yes,” Chai said. “10 anti personnel mines and 14 UXOs.”

Where, I inquired. “Where we just came walking,” Chai replied. “Yesterday.”

This news seemed to silence Somet who, sitting down in a folding chair, looked blankly off into the scrubby jungle. Four years earlier, Tobias had asked him about mines in this area, but Somet had assured him there were none left. “No, no mines here! No mines here!” Now this CMAC crew had revealed the hidden truth: Had Tobias or his engineers strayed this way to clear the canals, they might have been maimed or killed. It was a thorn in his friendship with Tobias, though it was not clear if he had betrayed Tobias, or if Cambodia itself had betrayed them both.

But Tobias said nothing now, and took photos of the men, the termite hill, the cases of UXOs that had been found, and the map showing the crew’s progress. He looked pale, perhaps from the heat. And he looked solemn and wasted.

Somet, who called me Father and who called Judith Mother, said nothing more. He held my hand as we walked back through the mine field towards the truck. He held my hand tightly, like a child who was frightened, but who was pretending that he was being brave. He is 34 years old – the age of our oldest son Dagan – and had grown up in this place: Knew it like the back of his hand. Tobias – who led us now back through the mine field – was 27. He walked casually, almost sauntering, across the ruts in the road, talking with Chai.

When we arrived back at the truck Tobias made an announcement. “I have to turn the truck around, and in order to do that I have to leave the road here. So I want all of you to stand back 30 feet while I do this.”

But the mines have been cleared, we said. There’s no danger now.

“They have swept for anti-personnel mines and UXOs”, Tobias replied. “They didn’t sweep for anti-tank mines, so you’ll have to wait while I turn this around.”

And then it was that I awakened from the dream of Cambodia into the realities of the place.

It’s one thing to visit the rubble of an ancient nation as it struggles to right itself from its long history of civil war and to marvel at the changes that are taking place. It’s another thing to visit the ruins of Khmer kings and Hindu temples and Buddhist monasteries that lay deep in the bush and contemplate the enormity of history that permeates the place. And it’s still another to walk a mine field where men in blue delicately scour the earth of plants so they might pick out the detritus of war.

But to watch your own son navigate the ruts of a road – not knowing what lay beneath the crust of red dirt as the wheels of the truck spin and the engine roars – is a transcending experience that focuses your mind to the present.

“One time, they set off an anti-tank mine,” Tobias had told me. “It was an explosion I will never forget.”

Here, there was no telling what might happen in this moment. But this time, there was nothing. Tobias threw the truck into reverse, and then pulled it from its rut, out onto the embankment just within the concrete markers. And so we climbed back in, drove the long red road back through the villages, through the fields of saw grass so sharp it can cut one’s arm, as naked children waved to us “hello, goodbye”, and women pulled their bicycles to the side to let us by. We drove two hours back into the city of Siem Reap. And then on to the airport where we boarded our plane and flew 30 hours home, here, safe.

The small Khmer lion on my step now has a different place in my mind’s eye. I now guess of what it is made. I now know that the dark patina of green will never shine like gold and that the days of the Khmer kings are over. No. This lion came from Cambodia, and is made of melted brass artillery shell casings, re-forged in a small hot fire by the side of the road, poured into a hand-carved mold in the red sands along the Siem Reap, and sent to market for a tourist to buy.

My son Tobias bought it for me, and now it guards my home.